The City Has Its Own Climate

What is the Urban Climate?

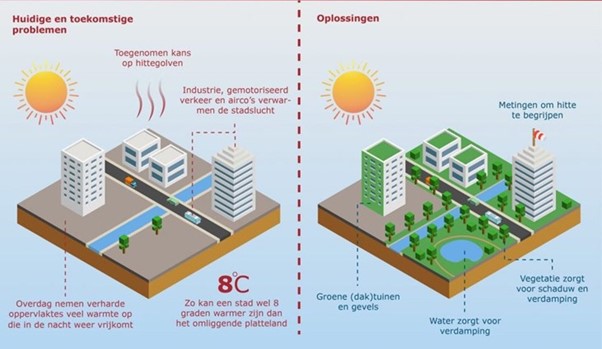

In the early 19th century, London chemist Luke Howard discovered that urban climates differ from their rural counterparts. After years of measurements in and around London, he observed higher urban temperatures, especially at night and during winter. This phenomenon was later named the urban heat island effect. The urban climate, characterized by higher temperatures and lower wind speeds, has become an important research subject, especially since more than half of the world’s population lives in cities. During the day, materials absorb solar radiation, and at night they release heat. However, the presence of buildings prevents this heat from escaping easily, and the lack of proper ventilation causes the heat to linger in the city.

Measuring is Knowing

Systematic measurements are essential to understand the urban climate and to create accurate models. These models are used for risk assessments and urban planning. Cities vary greatly: some are large, others small; some are densely built, others have many parks. It is important to monitor these variations and their urban climates. The meteorological VLINDER network provides valuable data in this regard.

As cities expand and become more densely built, the intensity of the urban heat island effect increases, leading to rising urban temperatures. This is compounded by global climate change. Therefore, cities must take action to remain livable in the long term.

Impact on Health and Comfort

In cities like Brussels, densely built areas can be up to 10 °C warmer than the surrounding countryside on a hot night. High temperatures cause heat stress, leading to poor sleep and reduced productivity. If someone cannot cool down properly, it can result in serious health issues like strokes, kidney failure, respiratory problems, and even death. The elderly and young children are particularly vulnerable on hot days and nights. Heat-induced sleep deprivation can also lead to aggressive behavior and lower work productivity.

Heat also increases energy consumption for cooling, which, if fossil fuel-based, contributes to greenhouse gas emissions. The heat island effect also warms urban rainwater, causing problems like algae blooms, fish deaths, and potential public health risks.

Greening to Cool

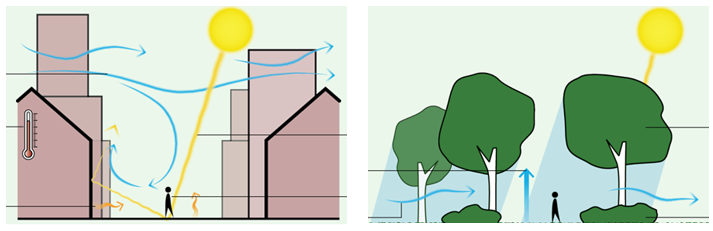

Reducing paved surfaces in cities is essential for cooling, with green spaces and trees being key to mitigating heat stress. They provide cooling by creating shade and evaporating water. In comparison to asphalt and concrete, plants retain less heat, helping cool the environment faster. Plants use solar energy to evaporate water from the ground, preventing the energy from being used to heat surfaces.

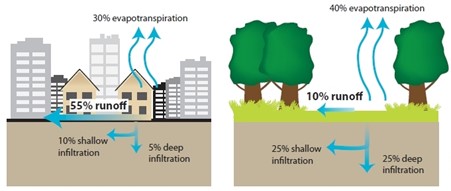

The illustration below shows the relationship between vegetation and evaporation.

Impact on Heat, Wind, and Water

The cooling effect depends on the amount of greenery and biomass. Larger trees with dense canopies cool more effectively than smaller ones. Vegetation also reduces water runoff peaks by holding rainwater and slowly allowing it to infiltrate the ground.

The Role of Water in the City

Urban water bodies provide cooling during the day but release heat at night if the water is stagnant. Flowing water cools the surrounding area better than still water. The combination of trees and water, such as ponds and fountains, is the most effective against heat stress due to shade and cooling.

Moreover, features like wadis—a type of natural buffer basin—help to capture rainwater and slowly allow it to infiltrate. This is important for maintaining groundwater levels during periods of drought.